A Dangerous Game: Secrets and Safety in “Dancing With Our Hands Tied”

How the threat of the truth coming out can alter the way you live your life.

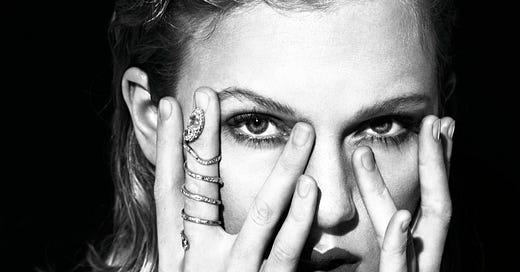

Taylor Swift has written countless songs about secret relationships throughout her career. The attention and pressures of a life of celebrity could explain this pattern, but her storytelling is not that simple. In “Dancing With Our Hands Tied,” the speaker fears for much more than just her reputation (the album it’s from). In this song, which Swift mashed up with “The Albatross” at the Eras Tour in June, she describes the potential exposure of the relationship as utterly catastrophic for both the speaker and the muse. A queer reading of the song allows for a nuanced analysis and understanding of the risks and stakes involved when this is a type of forbidden love.

Young and Naive

Swift begins the first verse by establishing several key details: “I, I loved you in secret / First sight, yeah, we love without reason / Oh, twenty-five years old / Oh, how were you to know? And.” Secrecy, and the resultant vulnerability, is the defining characteristic of the relationship between the speaker and the muse. Their instant connection at “[f]irst sight” stops them from considering “reason” or the challenges of pursuing a secret sapphic relationship. The speaker blames this, in part, on either her own or the muse’s naivete at age “twenty-five.”1 Swift, who was 27 at the time of the song’s release, treats this as the reason that they were both oblivious to the fact that the situation would become so difficult. These first lyrics are made up of fragmented ideas, including an incomplete question, so the listener has to fill in the gaps themself. By barrelling on with the next thought in the same line (“how were you to know? And”), the speaker calls attention to the scattered nature of the information provided, leaving the listener with more questions than answers.

The speaker then marks this relationship as distinct from her past experiences: “My, my love had been frozen / Deep blue, but you painted me golden / Oh, and you held me close / Oh, how was I to know?” This time, the question shifts focus to the speaker’s own naivete, apparently on account of her proximity to the muse. Despite being a source of comfort, the fact that the muse “held [her] close” also guarded her from judgement and from seeing through to the outside world. In this relationship, the speaker embraces the “golden” feelings that literally and figuratively contrast the “blue.” Swift uses the enjambment in “frozen / Deep blue” to effectively freeze the sentence and emphasize this despair in the vocal pause, as if the completion of the phrase is an afterthought. Her use of the less concrete “love,” as opposed to “heart,” for example, highlights its active nature and the fact that freezing it would not only result in sadness, but also bring her ability to “love” to a complete standstill. The muse, however, “painted [her] golden,” transforming her into a better, happier version of herself. Colors hold patterns of significance across Swift’s discography, especially blue and gold, which she often uses to characterize contrasting feelings. Most notably, “Daylight” describes the realization that “love” is “golden like daylight,” and, in an inversion of the first image, “All Too Well (10 Minute Version)” poses the question: “did the twin flame bruise paint you blue?” In general, gold, light, and color can function as representations of queer love and thematic opposites to blue, black, white, and gray, but this song is the most explicit example of this contrast.2

This Love Is Ours

In the pre-chorus, the speaker reflects on how she and the muse were hiding their relationship in plain sight: “I could’ve spent forever with your hands in my pockets / Picture of your face in an invisible locket / You said there was nothing in the world that could stop it / I had a bad feeling.” She contemplates spending “forever” together on account of their physical closeness and the feeling of belonging with each other. Putting your hands in your pockets is a natural, often subconscious, action, so having “your hands in my pockets” demonstrates a high degree of comfort. The speaker imagines that she could have happily kept the relationship secret forever, with an “invisible locket” as a symbol of their love that the world would never see.3 The muse “said there was nothing in the world that could stop it”; the meaning of this lyric is deliberately ambiguous. The word “it” could refer to their contentment together, suggesting that the muse wholeheartedly believed that their love would get them through any obstacles they faced. However, the line could also mean that nothing could stop the truth from coming out eventually, which might end their relationship altogether. Either way, the speaker “had a bad feeling” and developed a more cynical perspective on the situation.

She further contrasts the relationship in private and in public: “And darling, you had turned my bed into a sacred oasis / People started talking, putting us through our paces / I knew there was no one in the world who could take it.” With the word “sacred,” Swift uses religious terminology to describe love and sexuality—this is a motif that has become increasingly prevalent in her discography since reputation. By applying this word to a secular topic, the speaker deifies the safety afforded her by privacy, which is all the more essential in the context of a closeted queer relationship. She refers to love in the private sphere as a holy space, in this case an “oasis” in a world full of gossip and prying eyes. As rumors of the relationship got out, suddenly everything they said or did became one great test. Once again, the third lyric has two possible interpretations: the speaker fears that the muse would not actually be able to handle the negative attention if the relationship were exposed and society in general would not approve of it.

Dancing With Danger

The chorus brings us to the title of the song: “But we were dancing / Dancing with our hands tied.” “Dancing” can be taken both literally and figuratively, representing being together, as a distraction from the “bad feeling,” but also the notion of being hesitant and dancing around something. In “cowboy like me,” dancing similarly evokes both excitement and danger: “you asked me to dance / But I said ‘dancin’ is a dangerous game.’”4 The crucial part of the metaphor is “with our hands tied,” which indicates that, like in the idiom, they had no control over the situation. The speaker describes the tension between being in love and not being able to reveal the true nature of the relationship with this impediment. At the same time, the lyric conjures the image of “hands” being literally “tied” together, which is reminiscent of “invisible string” in its optimistic discussion of fate as being physically intertwined. The idea that this relationship is unique and special is evidenced by the fact that they’re dancing “[l]ike it was the first time.” Reflecting a common sentiment for a person’s first sapphic relationship, the speaker is with someone who makes her feel like she is experiencing love for the first time.

Stay With Me?

In the second verse, the speaker toys with the prospect of staying together through the hardships: “I loved you in spite of / Deep fears that the world would divide us / So, baby, can we dance / Oh, through an avalanche?” She voices her courage to love in the face of fear, wondering if the muse will do the same and “dance” with her in the worst case scenario. The speaker’s expectation that the “world would divide” them if the truth came out indicates that this is not just a secret love—it’s forbidden by societal norms. By suggesting that they “dance” together “through an avalanche,” the speaker asks the muse not to leave if the truth comes out. Here, and in the bridge, she compares the public disclosure of the relationship to a natural disaster. These lyrics demonstrate that, although internalized homophobia and a deep-rooted fear of social rejection still inform her decisions, she is inspired by the power of queer love and resistance in the face of adversity.

The speaker begs the muse for reassurance amidst her doubts: “say that we got it / I’m a mess, but I’m the mess that you wanted / Oh, ‘cause it’s gravity / Oh, keeping you with me.” She is quick to acknowledge her own imperfections but reminds the muse that she’s “the mess that you wanted.” The muse knew the risks going into the relationship, and now the speaker’s insecurities have escalated in the face of their potential outing as a couple. She claims that “gravity” keeps them together—an undeniable force of attraction and constant bond. The order of “you with me” suggests that the speaker is the center of gravity, pulling the muse back to her and holding on through the difficulties. Through the placement of and rhyme between these words, Swift equates “you with me” with “gravity,” a single word embodying power and cohesion. Despite the majority of the song narrating the story in the past tense, this verse implies that the two characters are still together, albeit not publicly. This is the only section in the present tense, its sense of realism signalling the speaker’s hope for navigating the future together.

Rain Down Fire

After the second chorus, the bridge introduces a hypothetical scenario: “I’d kiss you as the lights went out / Swayin’ as the room burned down / I’d hold you as the water rushes in / If I could dance with you again.” The speaker lists these catastrophic events, asserting that she would still be with the muse if the power went out, they were trapped in a fire, or in a flooding room. She relies on the muse for a feeling of reassurance when faced with disaster and, ironically, even feels protected by these circumstances. Kissing and embracing during life-threatening situations is a human instinct, but these lyrics also call back to secrecy in that they are safe to kiss each other in the darkness, when no one can see. By likening the relationship being outed to catastrophic events like fire and flooding, Swift renders the stakes extremely high, like a person being outed as queer in a dangerous environment. In fact, the image of raining fire is a Biblical symbol of divine punishment for sin, so here the speaker embraces this condemnation with the hope that sapphic love will conquer public discrimination and hatred. In this bridge, the “if” clause doesn’t come until the fourth lyric, before the entire sequence is repeated, retroactively clarifying the terms of these conditional phrases.

This keyword indicates that the speaker and the muse cannot “dance” together anymore, meaning that they got too close to the truth coming out, perhaps through their own recklessness and the illusion of being comfortably carefree. Whereas they used to run in each other’s circles without being perceived as a couple, they now have to retreat further into privacy in order to stay together. Looking at all the parts of this song, it seems to come from a perspective of maturity and reflection, mourning the speaker’s hope for societal acceptance in her youth. Although she doesn’t say that the relationship has ended, an aspect of it has in her resignation to love safely but silently. Ultimately, the crux of the song is that “dancing” is the thing that both gives the relationship strength and makes it vulnerable to public speculation and condemnation. By the bridge, the speaker realizes that it shouldn’t happen again, but if it did, it would be the way to attempt to get through these external challenges. Unfortunately, the internal struggle for queer people between self-preservation and self-determination is an ongoing issue when social circumstances and “the world” leave their “hands tied,” forcing people to continue loving each other “in secret.”

thanks for reading this essay on no, but listen! i’m happy to share my work for free, but if you’ve been enjoying my writing and would like to show your support, please consider making a one-time contribution below

you can also like, comment, subscribe, and share my work on substack or beyond! thank you for being here:)

This lyric was the inspiration for posting this essay, because my bestie is 25 today! Happy birthday, Nikoo!!!

The following are additional examples of gold and blue motifs:

"invisible string": "One single thread of gold tied me to you"—reminiscent of "hands tied"

"So It Goes": "Gold cage, hostage to my feelings"—the speaker is trapped on account of her feelings of love

“Dress": "Made your mark on me, a golden tattoo"—again, the lover is turning the speaker golden

"Cruel Summer": "It's blue, the feeling I've got"

"Lover": "My heart’s been borrowed and yours has been blue"—a play on the wedding saying as well as an allusion to past heartbreak

The locket image goes all the way back to Red, in "Sad, Beautiful, Tragic": "I stood right by the tracks, your face in a locket." There’s also another connection to “So It Goes”: “Wear you like a necklace.”

There are additional examples in Midnights:

"Maroon": "The one I was dancing with in New York"—dancing is once again a loaded word

"High Infidelity": "dancing around it"—dangerously sidestepping the truth

So honored to be the inspo behind this essay I love you